Why the automotive industry is pointing headlights at suppliers in the race to cut carbon emissions

As efforts to decarbonise the automotive industry shift gear, suppliers will need to improve their carbon management – and help is round the next bend.

Drivers can see the electric car revolution approaching fast, but it’s already appearing in the rearview mirror for automakers.

The heavy lifting on powertrain technology is done. Sales are rising, and the tipping point when battery electric vehicles (BEVs) outnumber internal combustion engines (ICEs) on the world’s roads is as good as baked in.

Since as much as 80% of a petrol or diesel car’s lifetime emissions come out of its exhaust pipe, manufacturers initially focused on the phase downstream of the dealership when the vehicle is racking up miles.

Now though, they are looking upstream. European Union leaders want a 55% cut in net greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, a ban on new petrol or diesel cars by 2035 and new legislation requiring batteries to be more sustainable.

If the big brands are to scrub up while honouring the Paris Agreement target, they must address their Scope 3 emissions embedded in materials high up in the value chain. And that means their suppliers do too.

Material world

Road transport generates 16% of global emissions, and eight out of 10 people living in cities are exposed to dangerously high levels of air pollution.

Consumer appetite for big, heavy cars is not helping; SUVs contributed more to the increase in global CO2 emissions last decade than iron, steel, cement and aluminium production combined.

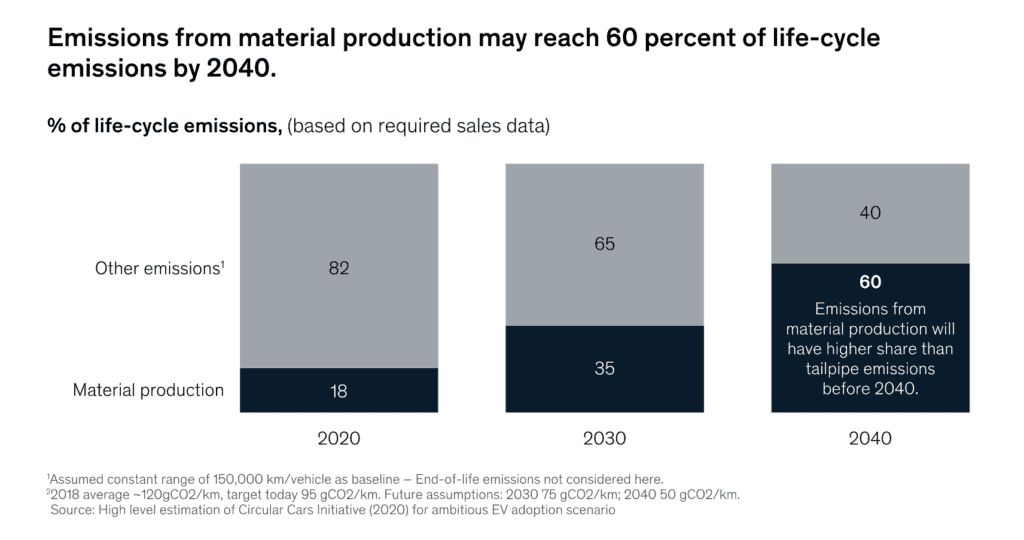

However, whereas material production accounts for only about 20% of emissions in a fossil-fueled car, for a BEV it’s close to double that, mainly due to the battery (World Economic Forum).

Consulting firm McKinsey estimates that by 2040 as much as 60% of a vehicle’s emissions will come from material production – unless major progress is made before then.

Fortunately, the firm also calculates that 97% of a BEV’s material emissions could be abated at no extra cost by 2030. Powering production processes with green electricity, recycling plastic components and using carbon-free (inert anode) electrolysis for aluminium extraction are some of the most cost-effective wins, it says.

About half the emissions associated with batteries could be abated by shifting production to regions with a low-carbon grid mix, according to McKinsey.

Tackling the steel sector – responsible for 8% of global CO2 emissions – will be more difficult. But producing steel from recycled scrap in electric arc furnaces will be cost-neutral over time, especially when mixed with virgin iron reduced with hydrogen (Direct Reduced Iron) instead of coking coal, adds the firm. If coupled with carbon capture storage and the use of biomass as a feedstock, steelmaking could ultimately become carbon-negative.

Alongside aluminium and plastics, ‘third generation’ steels with micro-alloys of manganese, molybdenum and silicon could make BEVs lighter, enabling them to go further on smaller batteries, adds the International Energy Agency.

2050 vision

There is no shortage of vision. Volvo-backed brand Polestar hopes to launch a fully climate-neutral car by 2030 using fossil-free steel from SSAB and zero-carbon aluminium from Hydro, both fellow Scandinavian firms. Its lightweight interior panels even contain corks from the wine industry – an idea copied from Hyundai supplier Seoyon.

BMW envisions its iVision Circular, due to be launched in 2040, will be a 100% recycled and 100% recyclable luxury compact car with quick-release fasteners so that it can be easily dismantled.

Mercedes-Benz recently unveiled the Vision EQXX, a super lightweight all-electric concept car with cactus-fibre seats, bamboo-fibre mats and panels wrapped in mushroom root instead of leather.

Retired Toyota Prius batteries have been powering an education centre in Yellowstone National Park, and several other manufacturers have given spent batteries a second life.

Meanwhile, Continental has been growing dandelions close to its tyre mills as a regional source of natural rubber rather than importing it from tropical regions – and Goodyear is following suit.

Swedish battery cell maker Northvolt already derives 98% of its energy from renewable sources, and Germany’s Vulcan Energy plans to use geothermal energy to pioneer lithium extraction in the heart of Europe with zero mining or emissions.

Road blocks

To prove that all this innovation is paying off, automakers need to be able to calculate the baseline of their Scope 3 emissions and then track progress year on year. And that’s no mean feat. A typical car contains some 30,000 parts provided by thousands of companies, the vast majority of which are far removed from the assembly line.

Compounding matters, the supply chain is in a high state of flux. Innovative new players are bursting onto the scene; old-timers are trialling new technologies in a bid to stay relevant. The Covid-19 pandemic and war in Ukraine have exposed frailties in the chain and sent raw material costs soaring.

To ease the headache, some car makers are cutting out links in the supply chain, following the example of Tesla, which makes its own batteries and sources raw materials direct from mining companies.

Accounting for the CO2 impact of every screw and thread in a car is an enormous task and one that neither the car makers nor their suppliers can do alone.

A 2022 survey of automotive suppliers by McKinsey found that while 83% had defined sustainability targets, only 7% had actually started to implement carbon emissions abatement programmes. And the World Benchmarking Alliance’s 2021 benchmark report of the 30 biggest car makers found that five had no climate-focused supplier engagement. Many of the others were too vague about what they expected from companies. Renault was the only company signed up to the CDP 2021 Science-Based Targets (SBTs) Campaign, which requests supply chain members set targets aligned with the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to well-below 2°C.

Full speed ahead

Help is just around the next corner, however. Dozens of car industry stakeholders, led by BMW, Toyota Motors, Volkswagen and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), have come together to launch A-PACT, the Automotive Partnership for Carbon Transparency. In August, this coalition is due to publish a methodology to help companies calculate the total greenhouse gas emissions generated by automotive parts over their life cycle.

AI-powered carbon management software will also come to the rescue, says Tom Wood, one of Emitwise’s carbon accounting experts, with over 15 years of industry experience.

“It’s a given that manufacturers and their suppliers must provide accurate financial data. The day is coming when they must provide accurate carbon data too. Auto suppliers that up their game and get an accurate baseline of their Scope 3 emissions now will have the competitive edge in the near future.”